The Image of the Journalist in Pakistan

State of the art GEO TV election set in Pakistan contrasts with the dangerous realities journalists face on the ground.

On Election Night in Pakistan, TV News was ready with teams of journalists, state-of-the-art sets and technical know-how to deliver the latest vote counts and analysis. The glossy image of world class media contrasted sharply with the reality journalists face on the ground in Pakistan: According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, at least 54 journalists have been killed in Pakistan since 1992. This year six men were convicted of murdering a Geo TV reporter, the first conviction since the beheading of US journalist Daniel Pearl in 2002. But the vast majority of attackers are never brought to justice. Journalists have taken to the streets, literally begging for their lives.

Pakistani journalists take to the streets to call for an end to attacks on journalists and demand the attackers be brought to justice.

When CNN producer Linda Roth and I were invited by the US Consulate in Karachi to teach in Karachi, Lahore and Islamabad in May 2014, these contrasting images provided the framework for our presentation on “The Image of the Journalist,” and set the stage for a spirited discussion of journalists’ safety and ethics in Pakistan. Americans tend to perceive journalists as either heroes or scoundrels. On the upside, we’ve got cultural images like Superman/Clark Kent and historical figures like Edward R. Murrow, superheroes who right society’s wrongs and champion the voiceless. On the downside we find Network’s Howard Beale, a victim of corporate greed and the battle for ratings. Or laughable buffoons like Anchorman’s Ron Burgundy and Ted Baxter of the Mary Tyler Moore Show, too caught up in their own egos to be of any use in serving the public interest. The image of the female journalist ranges from the sob sisters relegated to the feature/lifestyle beat, to the faithful sidekick Lois Lane, to the upbeat Mary Tyler Moore and the downright evil anchor bunny played by Nicole Kidman in “To Die For.” Drawing on materials from USC’s Center for the Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture, I shared a quote from Professor Joe Saltzman in my book, Power Performance: “Most films about journalism end with the reporter or editor winning the battle if not the war. If the journalist uses the power of the media for his or her own personal, political or financial gain, and the result is not in the public interest, then no matter what the journalist does, evil has won out. Without journalists, no democracy can survive. It is important to do the job of a journalist well. If you do not serve the public interest, you are in for a bad time.”

With Linda Roth of CNN, whose experience in conflict zones was invaluable in our discussion of journalists’ safety.

The concept of serving the public interest touched off a lively debate among the Pakistanis in our seminars. With at least 80 different channels providing 24-hour news and public affairs programming, competition is fierce. Fair and independent reporting of verified facts is often a casualty of the battle for viewers and profits. Pakistani journalists say they feel compelled to serve the interests of their owners or risk losing their jobs. Truth-telling runs the risk of offending sinister forces likely to express their disapproval with threats, guns and bombs. Linda’s presentation on reporter safety emphasized following your instincts to stay safe in a danger zone, but Pakistanis insisted it was not an option for reporters who will be fired or demoted to the bridal show beat unless they put themselves in harm’s way. Keeping your job and staying alive are important considerations that can push the public interest to the bottom of the priority list. An anecdote that resonated with the Pakistanis was the 1976 murder of Arizona newspaperman Don Bolles. He was reporting on organized crime in Phoenix when someone placed a bomb under his car, fatally injuring him. What happened next? A team of reporters gathered in Arizona to finish what Bolles was doing. The message: You can kill a journalist but you can’t kill the story. The Pakistanis applauded this idea and many shared it on Twitter and Facebook, but togetherness is not their strong suit.

A PFUJ gathering in Karachi showed how powerful Pakistani journalists could be if they could speak with a unified voice.

There are competing organizations that claim to represent the profession of journalism, but their leaders are not always willing to put rivalries aside to speak with one voice. As a result, some journalists actually welcome the possibility of a code of ethics imposed on journalists by the government, due in part to their inability to come together and agree on their own standards of fair and independent reporting. When newsman Hamid Mir survived an assassination attempt, wall-to-wall coverage on GEO news included accusatory statements from the victim’s family. For competing stations, it was merely an excuse to jostle for a bigger share of the audience, implying that the victim deserved it.

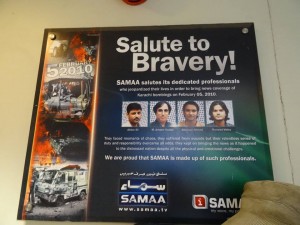

A sign in the Samaa TV newsroom in Karachi honors fallen colleagues.

But the danger is real. Newsrooms post pictures as memorials to their fallen journalists. Participants in our seminars told of dodging gunfire during live shots or being injured while covering bomb blasts. Brave Pashtun reporters had to come to us in the relative safety of Islamabad because it is too dangerous for American trainers to go to Peshawar.

Journalists from Peshawar had to come to Islamabad for training. Many senior journalists say they are ready for something more than another one-day seminar.

Nearly all of our trainings were held in the security cocoon of a western hotel or diplomatic compound. Since our training program in May, the June attack on the Karachi airport and updated travel warnings from the US State Department indicate that the situation may be getting worse. Yet, there are reasons for hope. Our meetings with student journalists revealed aspirations to a higher standard of ethical conduct and factual, balanced reporting.

We were impressed with the energy and talent of journalism students in Lahore.

Women journalists, who have endured discrimination and harassment on the job, have forged some common bonds. Exchange programs with the US and other free-press countries have created a growing core group of journalists who “get it.”So what next? While the evaluations of our program were overwhelmingly positive, many Pakistanis feel they’ve reached the point where they don’t need another certificate from a one-day seminar to hang on the wall. They need international, experienced mentors who are willing to guide them in the long-term as they develop their own brand of fair and independent journalism. Owners and senior executives of media companies need to get the message that images count: integrity is good for business and dead journalists are bad for the bottom line. A code of safety and ethics, adopted and enforced by journalists themselves and their news organizations, would be a good place to start.

A gathering of women journalists in Karachi revealed areas of common ground.

Tweet

Hi, I'm Terry Anzur. I've been a professional multimedia journalist for more than 30 years, anchoring and reporting everywhere from New York to Los Angeles to West Palm Beach. I've taught on-air skills to journalists of all levels, both through positions at the University of Southern California and Pepperdine University and through my own independent company.

Hi, I'm Terry Anzur. I've been a professional multimedia journalist for more than 30 years, anchoring and reporting everywhere from New York to Los Angeles to West Palm Beach. I've taught on-air skills to journalists of all levels, both through positions at the University of Southern California and Pepperdine University and through my own independent company.